Thomas Pogge, one of the world’s most prominent ethicists, stands accused of manipulating students to gain sexual advantage. Did the fierce champion of the world’s disempowered abuse his own power?

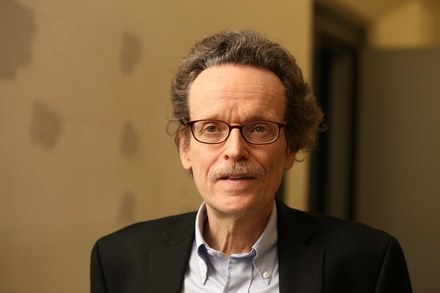

When Thomas Pogge travels around the world, he finds eager young fans waiting for him in every lecture hall. The 62-year-old German-born professor, a protégé of the philosopher John Rawls, is bespectacled and slight of stature. But he’s a giant in the field of global ethics, and one of only a small handful of philosophers who have managed to translate prominence within the academy to an influential place in debates about policy.

A self-identified “thought leader,” Pogge directs international health and anti-poverty initiatives, publishes papers in leading journals, and gives TED Talks. His provocative argument that wealthy countries, and their citizens, are morally responsible for correcting the global economic order that keeps other countries poor revolutionized debates about global justice. He’s also a dedicated professor and mentor, at Yale University — where he founded and directs the Global Justice Program, a policy and public health research group — as well as at other prestigious institutions worldwide. By Pogge’s own count, he’s taught 34 graduate seminars, given 1,218 lectures in 46 countries, and supervised 66 doctoral dissertations.

But a recent federal civil rights complaint describes a distinction unlikely to appear on any curriculum vitae: It claims Pogge uses his fame and influence to manipulate much younger women in his field into sexual relationships. One former student said she was punished professionally after resisting his advances.

Pogge did not respond to more than a dozen emails and phone calls from BuzzFeed News, nor to a detailed letter laying out all the claims that were likely to appear in this article. Yale’s spokesperson, Thomas Conroy, declined to comment.

Thomas Pogge Wikipedia / Tobias Klenze / CC-BY-SA 4.0 / Via commons.wikimedia.org

The allegations against Pogge are an increasingly open secret in the international philosophy community, an overwhelmingly male field in which, many women say, pervasive sexual harassment is an impediment to success. But for the first time, confidential documents obtained by BuzzFeed News reveal the extent of the claims against Pogge.

In the 1990s, a student at Columbia University, where Pogge was then teaching, accused him of sexually harassing her. In 2010, a recent Yale graduate named Fernanda Lopez Aguilar accused Pogge of sexually harassing her and then retaliating against her by rescinding a fellowship offer. In 2014, a Ph.D. student at a European university accused Pogge of proffering career opportunities to her and other young women in his field as a pretext to beginning a sexual relationship.

Yale has known about these allegations, and others, for years. When Lopez Aguilar first reported Pogge for sexual harassment, she said, Yale offered to buy her silence with $2,000.

Eventually, a hearing panel did find “substantial evidence” that Pogge had acted unprofessionally and irresponsibly, noting “numerous incidents” where he “failed to uphold the standards of ethical behavior” expected of him. But the panel voted that there was “insufficient evidence to charge him with sexual harassment,” according to disciplinary records.

More recently, Yale received letters from concerned professors and students at other institutions providing further evidence of Pogge’s alleged misconduct and asking Yale to reinvestigate. But Yale said those allegations were outside of its jurisdiction and that it would not reopen the case. Pogge is still at Yale, directing the Global Justice Program and teaching philosophy and international affairs classes on the New Haven, Connecticut, campus.

When Lopez Aguilar first reported Pogge for sexual harassment, she said, Yale offered to buy her silence with $2,000.

In October 2015, Lopez Aguilar filed a federal civil rights complaint, alleging that Yale violated Title IX, the statute that holds schools responsible for eliminating hostile educational environments caused by sexual harassment. Lopez Aguilar is asking the government to investigate whether Yale has ignored the “exhaustive attempts” she and others have made to prove Pogge is a danger to female students.

Her complaint also accuses Yale of violating Title VI, which prohibits race discrimination, on the grounds that Pogge specifically targets foreign women of color who were unfamiliar with how to navigate power in the United States.

The claims against Pogge pose critical questions about how universities manage the power dynamic between faculty members and students.

But they also raise questions that are more, well, philosophical.

Can someone fight tirelessly to balance the inequities of global power while at the same time abusing his own power? And can a discipline built on the quest to describe a just society — and suffering from a major diversity problem — afford to ignore these issues?

Fernanda Lopez Aguilar Susana Raab for BuzzFeed News

“If you don’t understand, who will?”

Lopez Aguilar grew up in Tegucigalpa, Honduras. She was a star student who published a book of poems about social justice at the age of 13; when she applied to college, her high school adviser wrote that she would one day be president. She enrolled at Yale in 2006, and took one of Pogge’s classes as a junior. When he agreed to supervise her senior thesis the following year, Lopez Aguilar was thrilled.

“It wasn’t even that he was famous,” said Lopez Aguilar, now 27. It was his commitment to morality and global justice, and the way he seemed to find his young students’ ideas as compelling as his own. “It inspired me to keep going.”

Pogge, then 56, and Lopez Aguilar, then 21, started corresponding about her thesis. Emails obtained by BuzzFeed News show that Pogge chided Lopez Aguilar for being too formal with him.

“Please don’t treat me like some porcelain primadonna,” he wrote when she said she hoped she wasn’t taking up too much of his time. When she said she was “forever indebted” to him for writing her a letter of recommendation, he told her to “cut it out.” When she apologized, he said he was “sorry for the scolding”: “I just thought you knew a little bit about me by now.” She assured him she did. “That’s a relief, Fernanda,” he wrote. “If you don’t understand, who will?”

She told herself it was normal to discuss her thesis on a bike ride with him and at his home, alone.

Lopez Aguilar said she felt a little uncomfortable, but chalked it up to cultural differences. So she told herself it was normal to discuss her thesis on a bike ride with him and at his home, alone. She thought it was strange that he wanted to crash at the Washington, D.C., apartment where she planned to live with her boyfriend over the summer — Pogge was “very tired” of wasting grant money, he explained — but she told him he was more than welcome.

When Pogge offered Lopez Aguilar work at the Global Justice Program, she eagerly accepted. Pogge listed her as a fellow on the program’s website and introduced her as a junior Global Justice fellow in an email to his colleagues, explaining that she would join them for a year of practical training after graduation. “Just tell me what you’d minimally need per month and I’d find a way to pay you that,” he wrote her in May 2010 when she asked about payment. “We’ll make it work out, don’t worry,” he wrote in another email. “I even have a little money of my own.”

Pogge also asked her to be his interpreter during a conference in Chile shortly after graduation, adding that she could stay in a hostel or was “welcome” to stay in his hotel room if she was “comfortable doing so; we can upgrade the room.” Lopez Aguilar said she didn’t want to make demands, so she offered to sleep on a cot or bring a sleeping bag, but she always expected that he would book them in separate rooms. When she arrived at the hotel, she found that there was only one, but still didn’t think it was her place to object.

“He was my mentor,” Lopez Aguilar said. “Now I see that I was naive, but I thought he actually appreciated me for my intellect. I was flattered that he saw promise in me.”

Only Pogge and Lopez Aguilar know what happened in that room, and Pogge has insisted to Yale he never made sexual comments or advances to her. But she later told the university that he asked her to join him in his bed to watch a movie, The Constant Gardner, on his laptop, with the lights off. That he said he couldn’t look at her in a black dress she wore because it was too “dangerous.” That he said perhaps she would consider marrying him someday. That he told the hotel staff to call them “Mr. and Mrs. Pogge.” That he mentioned he had been accused of sexual harassment at Columbia, and said she was “the Monica Lewinsky to his Bill Clinton.”

Lopez Aguilar said she tried her best to get through the trip, but one night as she sat at a desk translating documents, she felt Pogge slide in behind her on her chair, press his erection against her and grab her breast.

She says he told her that he couldn’t look at her because her dress was too “dangerous,” and that she was “the Monica Lewinsky to his Bill Clinton.”

She fled the room but had nowhere to go, she would later tell Yale. When she came back, Pogge said nothing.

“There’s something not natural all of a sudden,” she frantically Gchatted to her boyfriend. “I’m not feeling comfortable.” She asked him to stay online as she slept.

On the flight back to the United States, Pogge fell asleep with his head in Lopez Aguilar’s lap. She said she couldn’t wait to leave him at baggage claim. But he was coming to stay with her in D.C. in just a few days, and she said she felt too intimidated to refuse him.

The visit was awkward. Nervous that her fellowship was in jeopardy, Lopez Aguilar said, she tried to change the tone with some effusive emails.

“I am still ecstatic and sometimes pinch myself thinking about all the doors that you’ve lately opened (philosophically, I mean) in terms of better structuring my notions and convictions.”

In July, she asked Pogge for a “theoretical” document she could show to a landlord to prove she was employed by the Global Justice Program. He wrote her one on Yale stationery, which stated she would start on Sept. 1, 2010, and would earn $2,000 per month.

Still, she said, she felt anxious about the arrangement, so she showed up to work two days ahead of that date — only to be told there was no record of her employment.

She showed an administrator her name on the website, along with the letter, and then emailed Pogge. His response was furious. “You got me into a huge amount of trouble, Fernanda, as I am not authorized to give out jobs to people on my own,” he wrote her. “You manage to destroy in an hour as much as I manage to build in months.”

Fernanda Lopez Aguilar Susana Raab for BuzzFeed News

Emails show that when Lopez Aguilar realized there would be no salary, she asked Pogge at least to pay her “whatever price you think fair” for the work she had completed that summer, providing $2,000 as an estimate. He refused, saying she hadn’t done enough work to deserve that much money. On September 7, he told her he did “not want GJP to receive further help from you, paid or unpaid.”

Lopez Aguilar said she was crushed: As she saw it, she had withstood months of unwanted, unprofessional behavior from a man she believed to be her mentor, only to be fired under bewildering circumstances after she had rejected his advances. She decided to report Pogge for sexual harassment. But she didn’t know whom to report him to. And according to her recent federal complaint, Yale officials told her she had no recourse since she was no longer a student and hadn’t ever truly been an employee.

Eventually, Yale offered her a $2,000 settlement, on the condition that she sign away her right to pursue further claims against Pogge or the university — or to tell anyone about Pogge’s behavior from “the beginning of the world to the day of the date of this Release.”

The federal government has said that it’s illegal to use conditional nondisclosure agreements in sexual harassment cases. But Yale treated Lopez Aguilar’s report as a workplace dispute, ignoring her claims of sexual harassment, her recent complaint states.

She signed the agreement. She said she didn’t think she had any recourse.

She told Yale that Pogge had slid behind her, but she did not specifically mention an erection, or his hands on her breasts.

The following spring, however, 16 other current and former students filed a Title IX complaint with the Department of Education claiming that Yale had failed to properly address their sexual misconduct claims. A formal investigation was opened. (It concluded that Yale had underreported incidents of sexual violence “for a very long time,” among other violations.) Their complaint had nothing directly to do with Pogge, but it motivated Lopez Aguilar to try again.

This time, she said, she was told the nondisclosure agreement she signed was not actually binding. So Lopez Aguilar filed an official sexual harassment complaint to Yale on May 17, 2011. She brought up the harassment accusation that Pogge told her he faced at Columbia, and wrote out her own side of the story in painstaking detail. She would later say she stopped short of the whole truth on one point: She said that in their hotel room in Chile, Pogge had slid behind her in the chair so that his “pelvic area” touched her buttocks, but she did not specifically mention an erection, or his hands on her breasts.

“I was still too humiliated to tell my parents about everything that had happened,” she now said. “I assumed Yale would find Pogge’s other actions unwelcome enough.”

“Playing the hotel room card”

Yale assigned an arbitrator and hearing panel to the case that fall.

Pogge told the hearing panel that he had indeed been accused of sexual harassment at Columbia, but that the allegation was false. Yale knew about it, he said, and an official “took great pains to investigate what had happened” before offering him a job.

“This was by far the most traumatic event of my life, as can be seen, for instance, from the gap it left in my publication record,” Pogge wrote.

Yale University’s New Haven campus. Bob Child / AP

As for his interactions with Lopez Aguilar, Pogge insisted he did not have “any non-professional relationship with or intentions toward” her, the arbitrator wrote in her report. Lopez Aguilar was a weak student, he said, who from the beginning had worked toward “relaxing the terms of the relationship.” He never meant to offer her a paying job, he wrote; she knew he was just trying to help her stay in the U.S. after college. Pogge never forced Lopez Aguilar to share a hotel room in Chile, he continued, or made any sexual comments or advances to her. He acknowledged that they watched a movie together on a bed and he slept in her lap during the flight home, but said both activities were Lopez Aguilar’s suggestion.

Given his “contribution of frequent flier miles to her trip to Chile and given my knowledge that her apartment was large and shared with her boyfriend,” Pogge wrote, he thought it was fine to accept her hospitality in D.C.

He said Lopez Aguilar knew the letter he gave her to show her landlord was fake, and asked the panel why he would have “agreed to supply the non-genuine job offer needed to solve her apartment problem” if he had “been disposed to retaliate” against her after their trip to Chile.

A hearing panel found “substantial evidence” that he “failed to uphold the standards of ethical behavior” for a mentor.

Perhaps, Pogge suggested, Lopez Aguilar had been planning to blackmail him by “playing the hotel room card.”

He wrote, “Her idea was evidently that Yale or I would prefer to pay Ms. Lopez rather than have some potentially embarrassing discussion of what this Yale professor was doing with his former student in a Chilean hotel room.”

The fact-finding arbitrator, a former judge who teaches at Yale, also spoke with students who said Pogge was perfectly professional.

The arbitrator concluded that “neither party was telling the whole truth.”

She wrote that Pogge had admitted it was “unwise” to “invite an undergraduate woman to his apartment when there was no one else present, to agree to share a hotel room with her for several days, and to sleep with his head on her lap during a flight.”

Pogge’s behavior was “at best confusing coming from a charismatic professor who was able to offer her an affiliation in an organization that interested her intensely, and at worst likely to make this young woman think that she was likely to be asked to have a close and perhaps intimate friendship,” she wrote.

She found his anger at Lopez Aguilar after she showed the letter he wrote her to the Global Justice Program “disproportionate to the events,” and said he provided “no credible explanation” for ever having said he would pay her a salary.

But the judge also said that Lopez Aguilar had minimized her own role in sending Pogge “intimate” emails and proposing meetings that resembled dates, and that those cheery emails after their trip made her story less credible. “It appears to me that Complainant’s reaction at being out of Respondent’s good graces in the fall of 2010 has led her to recast some of the earlier interactions,” she wrote.

A subsequent hearing panel found “insufficient evidence” to determine whether Pogge had made direct sexual comments or advances to Lopez Aguilar, but “substantial evidence” that he “failed to uphold the standards of ethical behavior” expected of him as her mentor and employer.

In the end, however, the panel decided his actions did not constitute sexual harassment.

Only one note went into Pogge’s permanent record. It was for misuse of Yale stationery.

An unexpected development

Afterward, Lopez Aguilar “fell apart,” she said. A psychologist later diagnosed her with post-traumatic stress disorder linked to Yale’s handling of her claims. In 2012, Lopez Aguilar hired Ann Olivarius, a lawyer and Yale alum who had also been the plaintiff in the first Title IX sexual harassment lawsuit against a university.

Her legal team found Columbia professors with direct knowledge of the sexual harassment proceedings that Pogge faced there.

“I falsely assumed that the man who calls affluent westerners human rights violators would treat women with dignity.”

In an affidavit quoted in Lopez Aguilar’s federal complaint, a Columbia professor wrote that Pogge “had written a series of sexually harassing emails” to a student, “and there had also been some physical interaction between them.” Pogge was later “forbidden by the university administration” to enter the philosophy department “whenever the student had classes there.”

(The unnamed student later left the program, according to the affidavit. BuzzFeed News was unable to reach her.)

Soon enough, Lopez Aguilar learned a whole lot more about Pogge and his relationships, but this time no legal research was required. In April 2014, the website Thought Catalog published an anonymous essay called “I Had An Affair With My Hero, A Philosopher Who’s Famous For Being ‘Moral.’”

“I should’ve never met my hero,” the author wrote, “because when I did I found out that, just like his mentor (another famous philosopher), he vehemently refused to subject the private sphere to assessments of justice. … I falsely assumed that the man who calls affluent westerners human rights violators would treat women with dignity.”

The author never named the philosopher, but described him as “an old man, occupying a powerful place in academia, who has a penchant for young, inexperienced women.” Commenters quickly guessed it was Pogge, and someone put Lopez Aguilar in touch with the writer.

“Aye,” a graduate student who had an affair with Pogge. She published an anonymous essay about it on the website Thought Catalog. Laura Gallant / BuzzFeed News

Aye, a philosophy Ph.D. student from one of the poverty-stricken Asian countries Pogge has written about, first met Pogge at a conference in Europe the year before she wrote the Thought Catalog essay. (She is identified by a nickname at her request.) Then 29, she said she was surprised when he tracked down her email address afterward, but told him she was a huge fan of his work. “I will always be cheering you from afar,” she wrote.

Pogge suggested that on a visit sometime he could “cheer” her “from a little closer.” He also said he hoped Aye would “perhaps join one of the enterprises I am also involved in.”

Aye was flattered but confused. “He didn’t know anything about my work,” she told BuzzFeed News. “All he knew about me was what I looked like.”

Pogge told Aye he lived alone and hadn’t had sex in years, she said. Emails confirm that they started non-monogamously dating, but the relationship soured when she found out he was in a decades-long relationship, and told her that he had had intimate relationships with other young protégés before. Aye told Pogge he was a hypocrite. How could he advocate “gender-sensitive” solutions to global power imbalances while exploiting the power imbalance between himself and the much younger, non-Western women who idolized him? In response, Pogge dismissed her in an email as “self-righteous” and said her objections were “gathered from feminist and petty-bourgeois sources.”

Aye wrote the Thought Catalog essay in a rage, she said. A recording obtained by BuzzFeed News shows that Pogge read it closely.

“Yeah, true, sure, everything is true,” he told her. “That’s how you experienced it. I’m sure that you are an honest person, that you’re trying to depict it as accurately as you can.”

Aye and Lopez Aguilar said they saw a pattern to their experiences, and joined forces to see if they could find other young students he had treated similarly.

In 2014, Lopez Aguilar’s lawyers sent Yale signed statements from professors about the Columbia incident. The lawyers also included statements from professors who had witnessed and been troubled by Pogge’s conduct with young women at conferences, as well as details about five other women, students at other institutions in countries from India to Norway to whom Pogge had supposedly offered plane tickets, hotel rooms, letters of recommendation, and job opportunities “even though he barely knows them and knows less about their work.”

One was a young Chinese student whom, Pogge told Aye, he had a relationship with. In a recording obtained by BuzzFeed News, he admitted that he wrote the woman a letter of reference despite never having had any real “intellectual contact” with her.

Aye Laura Gallant / BuzzFeed News

Another Chinese woman wrote a statement for Lopez Aguilar’s lawyers saying Pogge offered her flights and a job despite being unfamiliar with her work. “To be honest,” she wrote, “I hadn’t worked with him that much that would qualify for me to go to work with him. Almost everything was a little inappropriate.”

Responding to the growing rumors about Pogge, Yale philosophy professor Jason Stanley made a public request for anyone with knowledge of Pogge’s professional misconduct, “even students in his areas at other universities,” to contact Yale’s Title IX coordinator, Stephanie Spangler. Aye wrote in to share her story and the information about other women. But Spangler told her it did not fall under Yale’s jurisdiction.

Separately, Lopez Aguilar said, Yale’s legal department informed her that the time during which she could have taken legal action had expired — and that she was a weak witness, given that she had previously taken medication for anxiety and acknowledged changing her account of that night in the hotel.

Yale “carefully considered” the evidence her lawyers sent, Spangler wrote to Lopez Aguilar in spring 2015, but would not reopen her case and had “nothing further to communicate.”

“Thank you for your expression of concern for the safety of the Yale community,” Spangler wrote.

“It can be crushing”

Universities have many reasons to keep sexual harassment investigations secret, including laws in some states that prohibit the disclosure of confidential information, and they take great pains to do so. But in recent years, there have been calls for greater transparency as an increasing number of schools have been accused of shielding high-profile faculty from the consequences of their actions.

“We’re currently going through a fraught and difficult period, as people are learning that they can’t get away with the behaviors that used to be taken for granted as normal,” said Jennifer Saul, the philosophy department chair at the University of Sheffield and editor of the blog What Is It Like to Be a Woman in Philosophy, which has posted anonymous stories about sexual harassment since 2010.

The relatively small field of philosophy has been rocked by sexual harassment scandals at least three times over the past two years, as male philosophy professors at the University of Miami, the University of Colorado, and Northwestern University resigned after being accused of misconduct by students.

Philosophy has a pervasive gender gap. The percentage of philosophy Ph.D.s who are women is lower than 30%, less than in most of the physical sciences, and research has found that top journals publish and cite far fewer women than men. For female philosophers of color, the situation is even worse.

Within that climate, aspiring female philosophers can find unwanted sexual advances from a potential mentor particularly devastating.

“It’s especially difficult for young, vulnerable people in the profession to report sexual misconduct by someone who supposedly is in their court,” said Ruth Chang, the American Philosophical Association’s sexual harassment and discrimination ombudsperson. “It can be crushing to discover that a famous professor who seemed genuinely interested in helping you grow as a thinker is really engaged in something rather different — whether it be getting his ego stroked or outright sexual predation.”

Yale “carefully considered” the evidence but would not reopen her case and had “nothing further to communi-cate.”

Because of the contracts that govern their employment, tenured professors who face sexual misconduct claims are much harder to discipline than students accused of similar offenses. This discrepancy can make for complicated proceedings, especially as the federal government has put pressure on universities to investigate and resolve sexual harassment cases without giving much guidance about what to do when the accused is a tenured faculty member.

Some universities have tried to get ahead of the problem by enacting blanket bans on romantic or sexual relationships between teachers and students. In 2010, Yale banned professors from pursuing “amorous relationships” with undergraduates, noting they are “particularly vulnerable to the unequal institutional power inherent in the teacher-student relationship and the potential for coercion.” But Yale didn’t appear to question whether Pogge violated that policy in his relationship with Lopez Aguilar.

Another complicating factor is that the universities that adjudicate cases like this are not disinterested parties. Even a single star professor raises a department’s profile, a fact that at least has the potential to influence decisions about discipline — or about hiring. “By adding a prominent scholar” in the field of global justice, said Brian Leiter, a philosophy professor at the University of Chicago who writes the definitive blog on faculty appointments in the field, “Yale is then a magnet for students, whether in philosophy or political science, interested in these questions.”

Leiter stipulated that he did not know the details of Pogge’s case, or the circumstances of his hiring. But he observed that as more of these once-secret accusations become public, professors may find themselves less insulated from the effects.

“These days, someone who has been credibly publicly accused is not hirable,” he said.

“It breaks my heart”

It has been a busy spring for Pogge. In late April, he spoke at the London School of Economics’ Africa Summit. On May 19, he talked about “effective altruism” at the University of Hong Kong, which advertised Pogge as “one of the most prominent figures in the contemporary academic debate on global justice.” In June, he’ll teach a master class at the University of Queensland in Australia, which called him “an exemplar of the best type of engaged political philosopher who tackles global problems and practices philosophically and practically.”

But the allegations against him have also traveled widely, in recent years, attracting attention in philosophy departments around the world. In 2014, a fundraiser for Lopez Aguilar’s legal costs raised over $7,000.

BuzzFeed News spoke with three women who have worked alongside Pogge, all of whom said he had treated them with respect. One said she felt personally injured by rumors to the contrary. They would not speak on the record.

But others said the news has forced them to re-evaluate the contemporary they thought they knew.

“There’s a sense of betrayal, and also shocked confusion,” said Monique Deveaux, a philosophy professor at Guelph University in Ontario. “How can we square what we’ve heard about Pogge’s conduct with his ideas on suffering and injustice?”

Louise Antony, a philosophy professor at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, pointed out the difference between the moral views of an individual and their ethical behavior: “The evaluation of the philosophical work — the quality of the arguments — is one thing, and the evaluation of the philosopher’s behavior is something else.”

“There’s a sense of betrayal, and also shocked confusion.”

She added, “We take our job to be giving students the tools to make good ethical decisions. But of course, a philosopher can know what the tools are, and still be bad at using them.”

Nonetheless, some said they feel a personal responsibility to try and curb his influence.

“It breaks my heart to have to say it,” said Christia Mercer, a former colleague from the Columbia philosophy department, “but it’s clear that Thomas uses his reputation as a supporter of justice to prey unjustly on those who trust and admire him, who then — once victimized — are too intimidated by his reputation and power to tell their stories.”

Martha C. Nussbaum, a professor of law and philosophy at the University of Chicago, said that since learning about the accusations Pogge faced at Columbia, she has chosen not to invite him to conferences and workshops. She also declines to participate in projects he is involved in.

“The time has come for a public investigation,” she wrote in a statement that Lopez Aguilar’s lawyers later gave to Yale.

That investigation may soon commence. The Department of Education recently informed Lopez Aguilar that her civil rights complaint is still under review. And this month the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, a separate government entity, said it would not conduct its own additional investigation, meaning the path is now clear for her to file a lawsuit of her own.

But Lopez Aguilar, now the spokesperson for a reformist political movement in Honduras, said she no longer holds out much hope that these processes will work in her favor. That’s why she also hopes to force a broader conversation about the way these cases play out, and the factors that might influence the way we view them.

Pogge uses philosophy as a powerful tool with which to solve global problems — a fact that greatly enhances the discipline’s real-world credibility. Could that have inclined his fellow philosophers to tolerate behavior they would otherwise condemn? Or is the discipline simply sexist?

Finally, what is our collective responsibility — to put it in the language of global ethics — when the flawed humans we enshrine as intellectual heroes are accused of being far from heroic?

In his writing, Pogge argues that the power imbalance between rich countries and poor countries is so great that poor countries cannot reasonably be said to “consent” to unfavorable agreements between them.

Lopez Aguilar’s civil rights complaint uses his words against him, saying he does not apply the same concerns “to the relationships he maintains with his female students.” By filing that claim, she explained in a recent conversation, she hopes to regain her own sense of balance. “There is power,” she said, “in surviving ugly moments.” •

Fernanda Lopez Aguilar Susana Raab for BuzzFeed News

Katie Baker is a national reporter for BuzzFeed News and is based in New York.

Source :

https://www.buzzfeed.com/katiejmbaker/yale-ethics-professor?utm_term=.kdyVbYMq1#.rxbnq4EVL

Other source of the same topic :

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethical_intuitionism#References