The US helped defeat fascism during World War II, but also relied on racial segregation as an instrument of wartime politics.

May 8 marks the anniversary of the end of World War II in Europe. Although Western nations remember this conflict as “the good war,” one in which the forces of freedom and democracy triumphed over fascism and racism, the truth is more complicated.

When the United States sent troops to Europe in 1942, both government and military shared a set of racist attitudes and a belief in America’s mission in the world. US President Franklin D. Roosevelt had declared that this was a war for four freedoms: freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom from want, and freedom from fear. The language of this declaration, laid out in the Atlantic Charter of 1941, was well known to European civilians and Americans, from top brass to lowest grunts, government ministers to ordinary people.

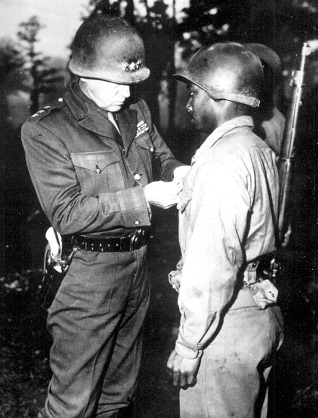

Yet despite Roosevelt’s condemnation of Adolf Hitler’s ideology, the government segregated its armed forces by race. US military and political leadership had declared African Americans unfit for combat service, relegating them to menial jobs. Black Americans served in the same proportion as their numbers in the population, ultimately forming about 10 percent of American troop strength. They were organized into separate units, training centers and clubs. Until 1950, the American Red Cross segregated black and white blood.

This Jim Crow segregation, a defining feature of US society since the late 19th century, was exported overseas during World War II. At home, wartime America experienced six civilian race riots and more than 20 military riots and mutinies. Abroad, soldiers often fought with one another, frequently a result of arguments over women or because white soldiers harassed black soldiers. One white soldier, responding to a postwar survey,described these incidents as “nigger hunts.” Many white soldiers, particularly those from Southern states, resented that the color line was more fluid in Europe than it had been in the United States.

Allegations of violence against civilians in Europe also dogged the military. Complaints of rape peaked in summer 1944 after the D-Day landings in northern France and again in spring 1945 as the Allies advanced into Germany. Omar Bradley, commander of the largest group of armies on the continent, warned Allied Supreme Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower in April 1945 that “certain conditions of looting, pillaging, wanton destruction, rape and other crimes” were widespread in enemy territory. A postwar report, “History of the Judge Advocate General’s Office” held in the Library of Congress, confirmed these concerns: “We were members of a conquering army and we came as conquerors. The rates of reported rapes sprang skyward.” Evidence of these admissions are in army records at the National Archives in Washington, DC.

Commanders in Europe recognized rape as a problem, but did not treat it seriously – instead blaming sexual crimes on black soldiers. In this way, the army’s race and gender problems became intertwined. Black GIs represented more than 40 percent of soldiers tried for rape and two thirds of those found guilty. In some countries, these figures reached staggering proportions: In France, black soldiers were 77 percent of those convicted of rape; 80 out of the 96 men the military executed for crimes in Europe and North Africa were black.

Army commanders described black soldiers as “bestial” and “barbarous,” while explaining away sexual crimes of white soldiers as “boisterousness” or “blowing off steam.” When white soldiers were accused of raping women and children in France in August 1945, just before the victory over Japan was declared, commanders held an investigation but did not prosecute.

After the war, politicians put trumped-up stories about the rape of white European women by men of color to political use. Rape allegations in the hands of white supremacists served to underline the unsuitability of black Americans for full citizenship – an effective way to forestall inevitable post-war battles for civil rights.

These racialized rape myths gained new traction with World War II. A 1945 letter from a white Southern woman to her local Georgia newspaper reflected this: “Read of how many of them had to be disarmed because of their attacks on defenseless white women of European countries,” she wrote, “read of their desertions from their ranks… Go read how many of those white boys died while the Negroes cowered in the rear.”

The racialization of rape had material consequences in the United States. Southern Democrats filibustered the Senate in 1945, in opposition to the Fair Employment Practices Committee, which had promised to end racial discrimination in federal employment. These politicians invoked rapes of European women in support of their arguments – and succeeded. Senator James Eastland from Mississippi repeated a well-worn lie, suggesting that black soldiers had disgraced the country: “I have been told that in any number of cities that decent white girls could not go out on the street because they would be accosted by groups of drunken Negro soldiers.”

These myths persisted despite fierce contestation by civil rights groups like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. When 14-year-old Emmett Till was lynched for whistling at a white woman in Mississippi in 1955, his killers were spared a second trial after white supremacists, among them Eastland, leaked details about his father, Louis Till, and his execution for rape in Italy during the war. The media portrayed Emmett as a rapist – “father like son like father,” as writer John Edgar Wideman reflected. The men who murdered the teenager walked free.

The US military’s success in racializing rape in Europe is evident in the extent of collective ignorance about sexual crimes committed by Americans during World War II. The military scapegoated black soldiers for rape while downplaying or ignoring the crimes of many white soldiers. While 4 million American soldiers passed under the jurisdiction of US military courts in Western Europe between 1942 and 1945, according to a June 1945 letter from General Eisenhower to Under Secretary of War Robert P. Patterson, 3.5 million of whom were whites of varying ethnic and religious identities. Ultimately, 461 were held responsible for rape: 205 white, 256 black. This is not evidence of an army’s exemplary conduct but of a concerted effort to sweep history under the rug.

The legacies of this history persist to this day. White supremacy, a perpetual feature of American history, is newly emboldened. Civil rights are under attack and violence against people of color is increasing. Black men remain overrepresented in rape allegations in the United States. In 2018, a white woman called the police on a 9-year-old African American boy whom she accused of sexually assaulting her when his backpack brushed against her in a convenience store. Racialized rape myths persist.

World War II was a race war. Nazi Germany fought for white supremacy and slaughtered millions of Jewish men, women and children. European nations conscripted African and Asian men to fight in support of their empires, which they ruled according to brutal racial hierarchies. Race similarly defined the war in the Pacific theater, where the United States and Japan deployed animalistic images of the other side in their wartime propaganda; during the war President Roosevelt signed executive order 9066, which led to incarcerationon American soil of 120,000 people of Japanese descent, two thirds of whom were US citizens. And for millions of African Americans, segregation of the military during the 20th century brought the race war to the home front.

The race war also had a gendered dimension. As writer Lillian Smith observed: “whenever, wherever race relations are discussed, sex moves arm in arm with the concept of segregation.” Rape was the fertile ground on which issues of racial segregation were weaponized and used as an instrument of wartime politics. The history of the good war is incomplete without acknowledging this aspect of our past.

By Ruth Lawlo*

May 3, 2019

Source :

https://www.eurasiareview.com/03052019-second-world-wars-legacy-of-racism-analysis/?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+eurasiareview%2FVsnE+%28Eurasia+Review%29

https://yaleglobal.yale.edu/content/second-world-wars-legacy-racism

*Ruth Lawlor is a Fox International Fellow at Yale and a PhD candidate in history at the University of Cambridge. Her research in US foreign policy focuses on conflict-related sexual violence and is supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, Cambridge Trust and the Robert Gardiner Memorial Fund.