كيف نحمي لبنان من مخاطر التطبيع مع "إسرائيل"؟

2025-11-25

كتبت الدكتورة عبادة كسر/ الحقول ـ بيروت : بعد "اتفاق" وقف إطلاق النار في 27 تشرين الثاني 2024، نشهد ضغوطاً أميركية كبيرة لإخضاع لبنان للخيارات...

إريك برينس، أشهر مرتزقة أمريكا، يستغل الفوضى الدولية

2025-11-25

ترجمة وتحرير الحقول / خاص ـ بيروت : قبل خمسة عشر عاماً، بدا مستقبل إريك برنس غامضًا.

الضبعة.. ننتظر الضوء

2025-11-24

كتب الأستاذ أحمد سعيد طنطاوي / القاهرة : في شمال مصر، حيث تختلط رائحة البحر النقي بصوت الريح، تنهض "محطة الضبعة"...

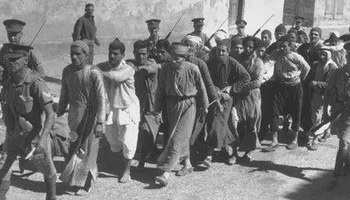

المقاومة في مواجهة حقبة الحسم

2025-11-24

كتب الدكتور حسام مطر/ بيروت : تشهد منطقة الشرق الأوسط، منذ عملية «طوفان الأقصى» في السابع من تشرين الأول 2023، هجوماً أميركياً واسعاً ضد محور...

البنية الخفيّة للقواعد الأميركية داخل "إسرائيل"

2025-11-21

كتب الأستاذ ياسر مناع/ الحقول ـ فلسطين المحتلة : في 11 تشرين الثاني 2025 نُشر تحقيقٌ صحافي مشترك بين موقع "شومريم" وصحيفة "يديعوت أحرونوت" كشف عن...

‹

›

الشؤون العربية

الضبعة.. ننتظر الضوء

2025-11-24

جدوى الحوار الإسلامي ـ الكاثوليكي...

2025-11-11

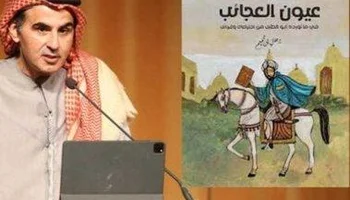

«عيون العجائب».. في عشق المتنبّي

2025-10-28