رسالة إلى المجلس الوزاري العربي : انتبهوا، فقد يخسر العرب حقهم في تقرير المصير...

2026-03-07

كتب الأستاذ علي نصّار/ خاص الحقول ـ بيروت : يعقد وزراء خارجية الدول العربية اجتماعاً طارئاً، غداً، الأحد، في مقر جامعة الدول العربية، في القاهرة،...

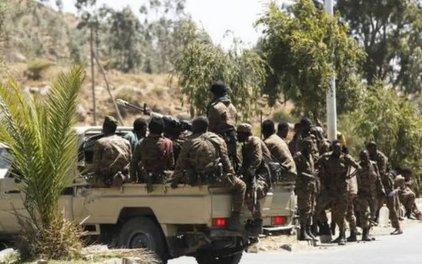

أثيوبيا استخدمت 4 تكتيكات لإخفاء فظائع جيشها في إقليم تيغراي

2026-02-15

شهدت منطقة تيغراي في شمال إثيوبيا واحدة من أشد النزاعات المسلحة فتكا في القرن الحادي والعشرين، فبين عامي 2020 و2022، قُتل ما يصل إلى 800 ألف شخص من...

How to get away with mass murder: 4 Tactics Ethiopia used to hide Tigray atrocities from the world

2026-02-15

The Tigray region in Ethiopia’s north has endured one of the world’s deadliest armed conflicts of the 21st century.

أوكرانيا "دولة إسلامية"؟!

2026-02-13

كتب محرر الحقول / خاص الحقول ـ الوطن العربي : فشل رئيس أوكرانيا فلاديمير زيلينسكي باستمالة "القادة العرب"، لدى حضوره قمة جدة بالمملكة العربية...

اليسار العربي و"العلاقة" مع تشومسكي "الإبستيني"!

2026-02-12

كتب الأستاذ علي نصَّار/ خاص الحقول ـ بيروت : تردد اسم الخبير في علوم اللغة، نعوم تشومسكي، في مصادر عربية منشورة، إبان النصف الثاني من ثمانينات القرن...

‹

›

الشؤون العربية

إسرائيل فى الصومال وباب المندب

2025-12-28

الضبعة.. ننتظر الضوء

2025-11-24

الشؤون الدولية

العرب والعالم

ما بعد "الأمم المتحدة"؟!

2025-12-27

المقاومة في مواجهة حقبة الحسم

2025-11-24

إيلاريون كبوجي..إيلاريون غزة

2025-11-11